How Valuable Has Ideological Analysis Been in Developing Your Understanding of the Themes of Your Chosen Films? [40 marks]

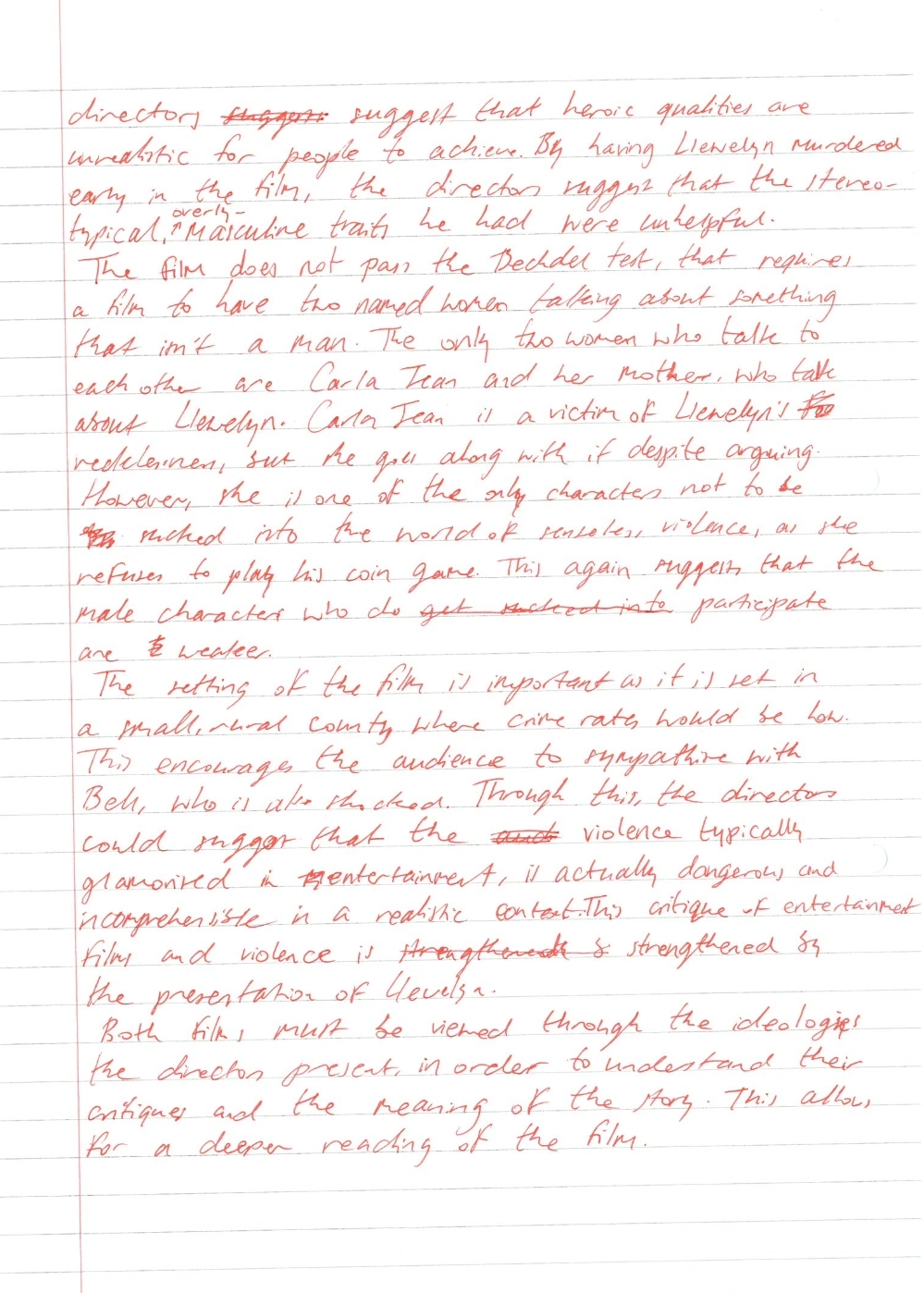

A specific world view is brought to each film in two ways: by the audience, including their expectations of what the film will look like, and their moral views of right and wrong, and also by the filmmaker, who has a specific world view as well, which is then presented through their film. Films can present an implicit, neutral, or explicit ideology. Winter’s Bone (Debra Granik, 2010) and No Country for Old Men (Joel and Ethan Coen, 2007) both present explicit ideologies, that go against the audiences expectations. It could be argued that both films present an ideology in favour of feminism, by either showing a world view from a female perspective, or by critiquing the typical presentation of masculinity seen in mainstream films.

Winter’s Bone is about seventeen-year-old Ree Dolly, who looks after her two younger siblings, Sonny and Ashlee, and cares for her ill mother. She must track down her father, Jessup, and convince him to appear at his court trial, otherwise her family will be evicted as their house was part of Jessup’s bond. She searches for him and is warned to stop by Thump, the local crime boss, she continues and is beaten by the women in his family. She’s rescued by her uncle, Teardrop. The women who beat her take her to her father’s bones in a swamp. They help her remove the hands from his body so she can prove his death. She gives the hands to the sheriff and escapes eviction, as well as receiving the cash portion of Jessup’s bond.

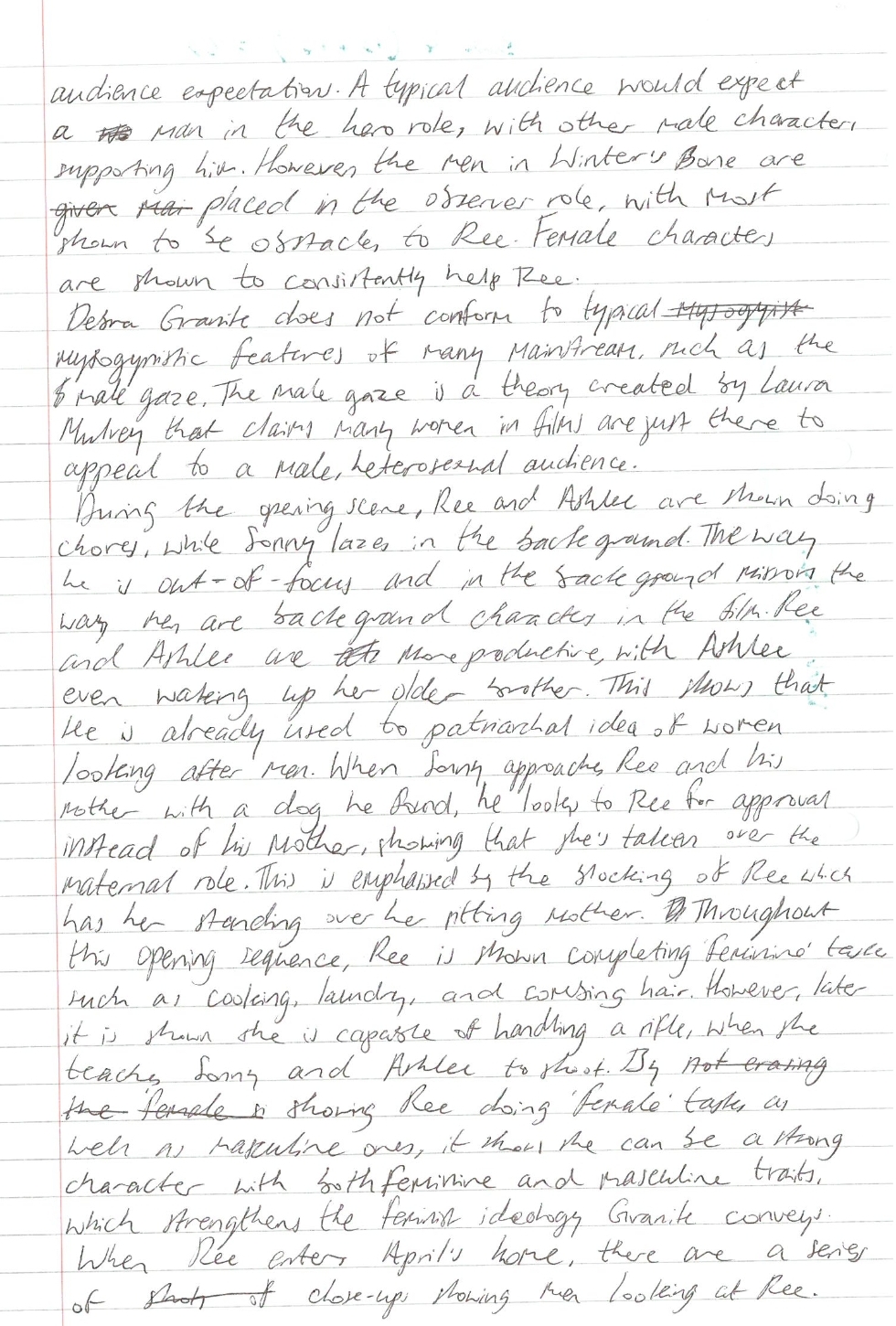

Winter’s Bone is an independent film, directed by a woman, with a largely female cast. The narrative is driven forward largely by the female characters in the story. This is not what an audience would expect from a film, as usually films are made up of mainly male characters, with little to no development of female characters. However, Winter’s Bone does not conform to these expectations, instead showing a female perspective through Ree, and showing other women helping her on her journey. There are male characters, but they are not given as much development or attention as the women in this movie, and most of the male characters are obstacles to Ree, with few exceptions. It could be argued that Granik presents a feminist ideology by not conforming to typical misogynistic features of mainstream films such as the male gaze, a theory developed by Laura Mulvey that suggests women are often presented to be visually appealing to heterosexual, male audiences. Ree, and most of the other women, are dressed in baggy, dark clothing, and most have their hair tied back for conveniences sake. It also passes the Bechdel test by showing named women having a conversation about something other than a man; this happens many times throughout the film and provides a more realistic and naturalistic view of life. In this way, the film goes against the audience’s ideology of what women in films typically look like. It may also go against their ideology of what a strong, female character looks like, as many presentations of strong or tough women in films erase all traditionally feminine traits in the character and replace them with traditionally masculine ones, mistaking masculinity for strength and femininity for weakness. Winter’s Bone, however shows Ree to be a strong person without hiding all traditionally feminine characteristics.

During the opening scene of the movie, Ree, Ashlee and Sonny are shown completing chores at their home. The children, Sonny and Ashlee, aren’t overly gendered in their costumes and the activities, both wearing baggy and neutral-coloured clothing, that looks typically masculine. This instantly establishes the fact that women and female characters are given the same level of importance as audiences would expect male characters to have. Out of the two children, Ashlee is given more screentime and is often the focus of close-ups and dialogue. For example, in the opening sequence, Ashlee is shown more often than Sonny and is also shown as more productive, helping Ree with the laundry and feeding the dog and is given a baby doll to care for, suggesting the burden of looking after a household is already being placed on her, as it was on Ree. This contrasts the way Sonny is presented, as he is often shown lazing around or playing with his skateboard, and has to be woken up by his younger sister in the morning, suggesting that he is already used to the patriarchal expectation of women taking care of the household. In a long shot of Ree and Ashlee hanging up laundry, Sonny can be seen out of focus in the background, with Ree and Ashlee in the foreground. This highlights the way men are metaphorically in the background of the film and shows women as being the focus of attention. It also shows the contrast in roles men and women have in this film, as Ree and Ashlee are being productive by doing a household necessity such as laundry, whereas Sonny is shown lazing in the background, not actively contributing. This mirrors the way women are more active in the story, whilst the male characters don’t do much to progress the narrative or help Ree.

Ree is presented as a maternal figure for the children, teaching them to cook and taking them to school. Ree also takes care of her ill mother, establishing the fact that she must care for her family alone, something that drives her to search for her father and also keeps her from things such as education, or from pursuing her dream of joining the army. This fact is emphasised by the way she views Ashlee’s class, a parenthood class, and an army training class, through the windows of closed doors, each representing education, family, and the army respectively. In the army training, however, the women march among the men. A mid-shot focuses on a woman marching with a gun in her hand, showing that there is some hope for Ree, however she is also shut out from the army later on.

When Sonny brings in a dog he found, he looks to Ree for approval instead of his mother, showing she has been accepted as more of a maternal figure than his actual mother. This is emphasised by the framimg of this shot, which has Sonny partially blocking his mother, so Ree is the focus. The lighting on the mother is also darker compared to Ree, making Ree stand out more, reflecting the way Ree has become more prominent while their mother has hidden away. He still leans in to let his mother pet the dog, showing he still seeks her attention. This is one of the only times we see Ree’s mother give a strong reaction to the children, and it is given to her son rather than Ree, who does everything for her, suggesting that her mother either sees her son as more important than her daughters, or sees what Ree does to help as an expectation rather than a burden she has given up so much to carry out. When the mother reaches out to pet the dog, Ree copies her movement, again aligning her as the mother figure. It also shows her learning from her mother, the same was Ashlee learns from Ree when she is shown following Ree around and watching her as she does laundry or cooks, suggesting a continued line of women being taught how to care for others, especially men. All these factors are used by Granik to show the expectations of women in Western patriarchal society, especially in the rural areas of America, which is juxtaposed with the freedom and lack of responsibility that the male characters, such as Sonny, enjoy.

In the rifle training scene, Ree decides to teach Sonny and Ashlee to shoot. This suggests that she might be concerned for their survival and is teaching them to protect themselves. It also shows how she is willing to take on more masculine tasks as she only the one around to do so and does not conform to stereotypical gender roles. By also showing Ree carrying out traditionally masculine tasks, such as shooting, as well as feminine ones, such as cooking and cleaning and caring for her younger siblings, Granik shows that women do not have to conform to the expected stereotypes typically presented, but also do not have to abandon them either, thereby showing feminine qualities being just as strong as masculine ones.

Throughout Ree’s teaching, Ash is more attentive than Sonny. However, it is Sonny who gets to shoot the gun, and is something he is successful at, showing his interest in more masculine activities. However, there is no reward for his shooting so shooting and violence avoids becoming glamorised, but is rather presented as a necessity for survival, either for protection or hunting. This is also emphasised by the way she focuses on their safety, and jumps when Sonny shoots, showing she is not fond of shooting.

As Ree arrives at April’s with Gail, she is faced with stares from a couple of men, with close-ups of men’s face showing them looking towards Ree, showing the audience the male gaze from the perspective of women, drawing attention to how invasive it is. This also puts men in the observer role as secondary characters, going against audience expectations. A woman is shown to be leading the music and conducts the other players, showing an environment where a woman is respected as authority. Ree stops to listen to the music as the woman sings about wanting to be a bird who can fly away, reflecting the way Ree wishes to escape by joining the army. When April, Gail, and Ree talk together, they sit alone as April gives Ree important information about her Father. This is one of many examples of women helping Ree complete her quest and driving the narrative forward. The focus on the three women also shows the bonds between them. April has a longer piece of dialogue in this scene, letting her hold the focus, showing her importance.

In the cattle market scene, Ree hunts down Thump Milton, who she knows to be dangerous, and follows him, trying to get his attention. Only men are shown to be present at the market, showing their control over money and business in patriarchal households, making Ree’s presence stand out as odd, highlighting the way she often participates in traditionally male activities. The imagery of the cattle shows them as cramped and panicked using mainly close-ups on the cattle to create a claustrophobic atmosphere, with the constant sound of diegetic mooing overlapping in the background creating a tense and stressed atmosphere. Parallels between Ree and these cattle are drawn to show her vulnerability. For example, the way her yelling gets lost in the sound of the cattle shows her insignificance to Thump, along with her sense of urgency. When she runs after him, images of cattles being herded are shown running in the same direction, suggesting that Thump is ‘herding’ her where he wants her to go, showing the control he has over her. The fence she runs behind is framed to look similar to the cages around the cattle, again showing that Thump has trapped Ree. It could be argued that this scene is an example of a stand off scene between a protagonist and the antagonist. However, Ree is unsuccessful, again subverting the audiences’ expectations.

The women in this story are responsible for drawing most of the narrative forward, which is something audiences wouldn’t expect. Granik does not conform to the male gaze theory, instead presenting the story from a woman’s perspective, which could be considered feminist as it places women in control of the narrative. However, she also shows the women dealing with problems caused by men, such as Jessup’s disappearance, showing that they aren’t living in a matriarchal society, but instead a more realistic patriarchal society, more similar to our western society. This keeps the story grounded in reality whilst also showing a non-conforming protagonist.

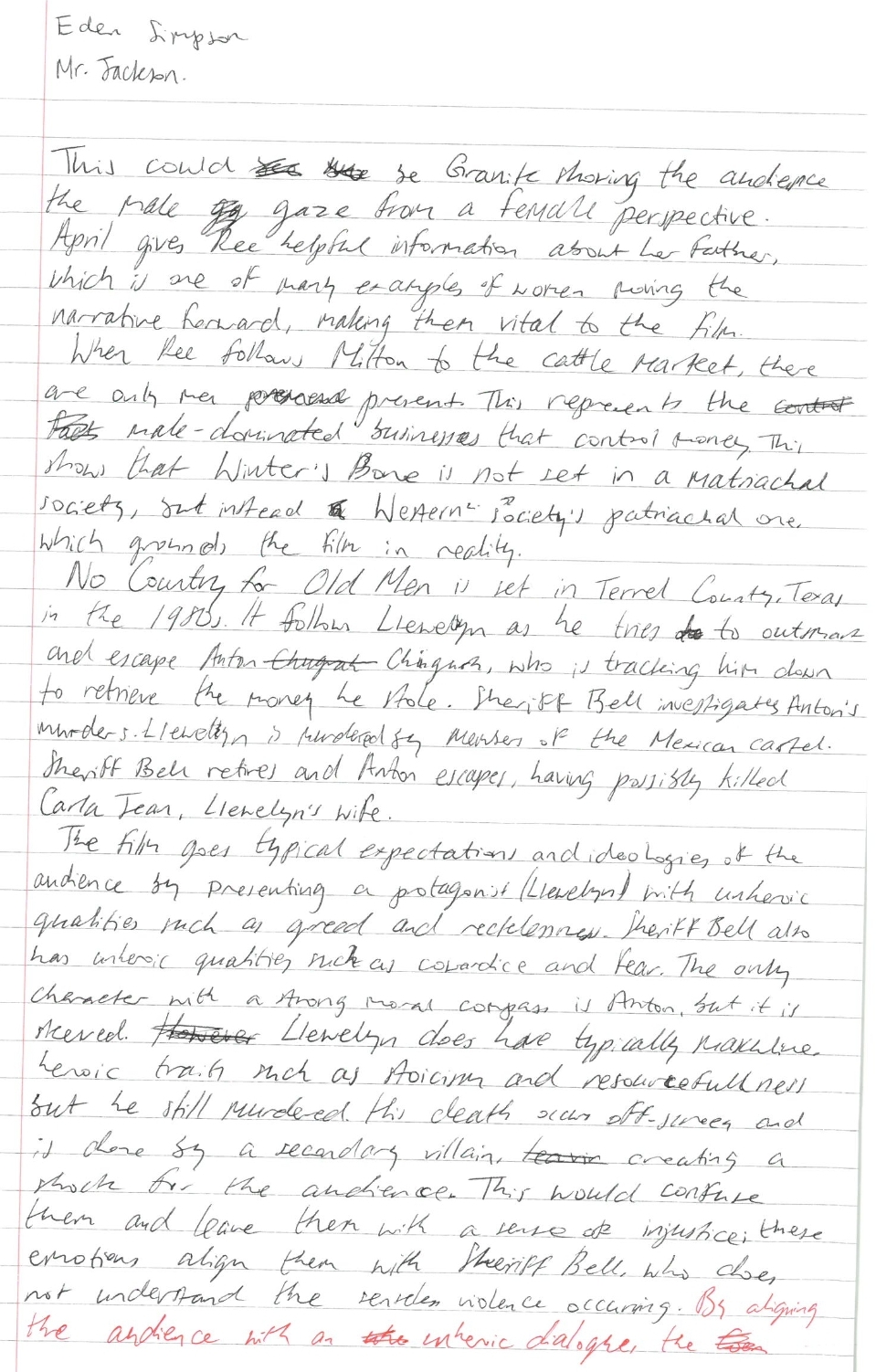

Set in Terrel County, Texas during the 80s, No Country for Old Men shows Llewellyn Moss’ struggle to escape and kill Anton Chigurh, after Llewellyn finds a case of money and Anton is hired to track it down. Sheriff Bell investigates the murders Anton carries out in Terrel County and tries to help Llewellyn’s wife, Carla Jean Moss. Wells is hired to find Anton and retrieve the money, which Llewellyn has hidden in Mexico. Wells is murdered by Anton, who threatens to kill Moss’ wife if he doesn’t give up the money, which Llewellyn refuses to do. Llewellyn is murdered by a group of Mexicans who were also following him. Sheriff Bell finds him after hearing gunshots and is there when Carla Jean arrives at the scene. Anton returns to the crime of Moss’ death and finds the money, Bell arrives as Anton is still there but Anton leaves before he is found. Bell visits his Uncle Ellis and tells him he is retiring; Ellis tells him time isn’t going to wait on him to catch up. Anton visits Carla Jean Moss, who has just returned from her mother’s funeral. She refuses to participate in his coin toss game, and it is implied that she is murdered too. As he leaves, Chigurh gets into a car crash but survives and exits the scene. The movie ends with Bell, now retired, describing his dreams to his wife.

This film does not meet audience’s expectations of what should be included in a mainstream film, for example, audiences would be used to the idea of a male protagonist with heroic qualities who defeats the villain a stand off in the third act, usually through typically masculine stereotypes such as violence and stoicism. However, Llewellyn is murdered about two thirds into the film, and isn’t even killed on screen, or even by the main villain. This would disorientate and shock the audience, leaving them with a sense of injustice and confusion, as would the sudden ending of the film that doesn’t provide a satisfying conclusion to the story. This serves to put them in the perspective of Sheriff Bell, who often feels that he doesn’t understand the senseless violence of the times.

The hero of the story, Llewellyn, often displays unheroic qualities such as greed, foolishness, and recklessness. The antagonist, Anton, seems to be the only character with a moral compass, even if it is skewed in comparison to what we’d expect. The sheriff also shows unheroic qualities such as cowardice and fear, as he is constantly reluctant to get involved and retires when he feels he cannot overcome the senseless violence he faces.

The setting of the film is important for emphasising how out-of-place and shocking the violence is for Sheriff Bell, because if the film was set in a city, where crime rates are often high, this violence would not be as shocking, but because it is set in a small rural town, similarly to Winter’s Bone, the brutality and violence is much more unsettling to audiences.

Whilst No Country for Old Men does not present a female perspective, it still challenges the typical toxic masculinity presented in most mainstream films, and therefore still presents a feminist ideology. The hero, Llewellyn, displays traits such as stoicism and pride that are associated with male heroes, but dies nonetheless, and the main character who survives unharmed, Sheriff Bell, is shown with unmasculine and unheroic traits such as fear, confusion, and reluctance. He is also the character that the audience is aligned with, as both are left without answers or the satisfaction of justice at the end of the movie, suggesting that heroic qualities are unrealistic for people to achieve, and it is more likely for someone to relate to the hopeless, lost perspective of Bell. However, even men who show kindness are also murdered by Anton, such as the man who offers to jump-start his car. This highlights the senseless, nondiscriminatory violence that Anton brings to the story, again causing the audience to sympathise with Sheriff Bell.

When Chigurh visits Carla Jean, the two have a lengthy conversation, shown in a shot/reverse-shot sequence, each character is given largely equal screen-time in this sequence, showing them to be on the same level. This scene importantly shows a character taking a different approach to Anton. Before, characters are usually shown speaking to Anton with fear or threats, and it is usually men shown talking to Anton like this. When they threaten him, as both Wells and Llewellyn do, this is a presentation of stereotypical masculinity that would be expected in mainstream films, however, this leads to both of the characters being murdered. Before Wells is killed, he attempts to bargain for his life, showing his fear of Anton. In this scene, Carla refuses to show fear and stays calm, holding her own against Anton and refusing to call the coin toss, insisting that he must make the decision. Although this likely leads to her death, it shows a female character showing more strength than most of the male characters did against him.

Anton is suddenly hit by a car whilst driving away, showing that he can also encounter the senseless violence he causes in an unexpected and unpreventable way, mirroring the way he kills without feeling or remorse. The shot of Anton driving does not show the oncoming car approaching, as most car crash sequences typically do, increasing the shock the audience feels, putting them in the perspective of Anton. After this crash, Anton is helped by two young boys, one of whom gives him his shirt, and refuses to take his money for it. This mirrors an earlier scene where Llewellyn pays a young adult for his shirt, who accepts the money and bargains the money upwards. This scene with Anton shows that, despite the amount of violence shown throughout the film, there is always a chance of encountering kindness, and it is presented by two kids, rather than the adults Llewellyn encounters, suggesting that there is also a loss of innocence as people begin to become more familiar with the world.

Both films present explicit ideologies to their audience, and both films challenge the ideologies audiences would bring the film. Therefore, it is important to consider these films along with these ideologies in order to fully understand the messages the filmmaker is trying to convey.